A note of interest: This video references the Waldorf curriculum's focus on Saints and Legends in second grade. Waldorf schools are not affiliated with any particular religion, but they do place emphasis on reverence of the "spirit" in the world around us--however that may appear to individual children. That being said, because the Waldorf movement came out of early 20th century Germany, many cultural traditions from that time and place are still observed in Waldorf schools, such as Saint Nicholas Day and Martinmas, and these traditions are overwhelmingly Christian in origin. Most Waldorf schools work diligently to ensure that traditions from other cultures are observed as well.

Friday, February 28, 2014

Waldorf Reading

Here is a brief video that talks about some of the literacy strategies common in the Waldorf curriculum. I recognize quite a few of them as strategies we have discussed in various courses this year. Enjoy!

A note of interest: This video references the Waldorf curriculum's focus on Saints and Legends in second grade. Waldorf schools are not affiliated with any particular religion, but they do place emphasis on reverence of the "spirit" in the world around us--however that may appear to individual children. That being said, because the Waldorf movement came out of early 20th century Germany, many cultural traditions from that time and place are still observed in Waldorf schools, such as Saint Nicholas Day and Martinmas, and these traditions are overwhelmingly Christian in origin. Most Waldorf schools work diligently to ensure that traditions from other cultures are observed as well.

A note of interest: This video references the Waldorf curriculum's focus on Saints and Legends in second grade. Waldorf schools are not affiliated with any particular religion, but they do place emphasis on reverence of the "spirit" in the world around us--however that may appear to individual children. That being said, because the Waldorf movement came out of early 20th century Germany, many cultural traditions from that time and place are still observed in Waldorf schools, such as Saint Nicholas Day and Martinmas, and these traditions are overwhelmingly Christian in origin. Most Waldorf schools work diligently to ensure that traditions from other cultures are observed as well.

Sunday, February 23, 2014

The Hundred Languages of Children

As you know, I am a self-professed Waldorf fanatic. I love most everything about Waldorf Education: the aesthetic, the warmth, the slow pace, the integration of art, music, and movement, the focus on rhythm, the respect for nature...I'll stop myself there, but I could wax poetic about Waldorf for many hours. There is one place that I have found Waldorf to be lacking, though: curriculum. Waldorf follows a very structured, prescribed curriculum through the grades. The content is based on Rudolf Steiner's philosophy of child development, and while I do think that some children live a path parallel to the Waldorf curriculum, many do not. Not all children grow or develop at the same pace, and not all children in seventh grade will be interested in the voyages of explorers (even if those children are embarking on the great voyage of adolescence).

Better and more inspiring in my eyes is the flexible, inquiry-based approach to curriculum found in Reggio Emilia schools. I find myself drawn back again and again to the amazing projects completed by Reggio students, and I decided to read more on the topic for this week's blog post. Jean Anne Clyde, a professor of education at University of Louisville, partnered with a group of elementary and early childhood educators to write the article, Teachers and Children Inquire into Reggio Emilia (published in Language Arts and accessible here). Clyde et al identify five distinctive characteristics of Reggio Emilia education:

1. Children as Protagonists of Their Own Learning

Howard Gardner describes Reggio's vision of children as "active, engaged, exploring young

spirits capable of remaining with questions and themes for many weeks, able to work

alongside peers and adults, welcoming the opportunity to express themselves in many

languages, to create new ones, and to apprehend and enter into those modes of expression

that are fashioned by their age mates."

2. The Hundred Languages of Children

This phrase, seemingly synonymous with Reggio, comes from a poem written by its

founder, Loris Malaguzzi. Malaguzzi describes children as possessing a hundred different

means to express their ideas and questions. In our literary context, I think we may rephrase

this as children having "a hundred literacies." Reggio students are encouraged to use a

multitude of media to describe their thinking, including (but definitely not limited to)

writing, drawing, photography, sculpting, and acting. Aligning with Gardner's theory of

multiple intelligences, different students will prefer different means of communicating. Part

of the Reggio teacher's duty is ensuring that students have easy access to the materials they

need, and the classroom becomes an atelier (studio).

3. Inquiry-Based, Long-Term Projects as Vehicles for Learning

As briefly explained above, Reggio Emilia does not operate on a curriculum, but allows

students to develop large, long-term projects based on their inquiry. Usually an inquiry topic

is followed by a whole class, and comes from student questions, often after observing a

spontaneous event, like a milkweed pod bursting into seed. The Reggio teacher helps guide

student inquiry through open-ended questions, but students take the reigns for how the

project progresses. Clyde et al write that "investigations result in real-life problem solving

among peers, and numerous opportunities for creative thinking and exploration."

4. Documentation as Communication: "Making Learning Visible"

One of the most time- and work-intensive responsibilities for a Reggio teacher is

documenting the process of student learning. As the students go about investigating and

exploring, the teacher collects physical artifacts of their learning (drawings, writing, etc),

and documents non-physical work through photographs, videos, and audio transcripts. All

of this information is then compiled into documentation panels, poster displays that work as

a timeline of student learning and documentation of the project's evolution. Documentation

panels can be viewed by administration, other teachers and students, parents, and--most

importantly--the students themselves, who often form new questions and ideas when

reviewing their previous work.

5. Teachers as Researchers and Collaborators

Reggio teachers are both guides and co-learners. They keep up with student questions and

ideas, and work to anticipate possible paths that projects could take. They work as

mediators, helping children to ask meaningful questions and develop goals for their

learning. They plan experiences that may trigger student inquiry, and they collaborate with

other teachers to build deeper understanding of students as learners and teachers.

(please note: If I were to make this list, I would also include a sixth characteristic: The Classroom as the Third Teacher. Reggio Emilia places great emphasis on the need for aesthetically pleasing, flexible spaces that allow students to freely explore their inquiry projects and enhance their ability to learn.)

Much like the situated literacy project The Donut House, Reggio Emilia projects treat literacy as a tool for investigation--a means to getting to the end, which is understanding and communication. Clyde et al describe an investigation by a first grade class into the mystery of an empty pond on the school grounds: "[The students] learned to read informational texts, use the index and table of contents, present information using various modes, and assert hypotheses. Their use of diagrams, labels, and drama to support their hypotheses was an efficient and effective way to apply principles of summarizing, analyzing, and accommodating information." For the students in a Reggio Emilia classroom, writing, math, and art are not subjects to be studied, but just a few of the hundred languages that students utilize when exploring their world.

The more I learn about the Reggio Emilia approach to education, the more inspired I become. I still have many questions to answer: What is the place of more traditional literacy instruction in Reggio? What does Reggio look like for older children? Like the students in Reggio schools, I will continue to strive to understand, and I'm sure I'll form many more questions on the way. But I do know that I am very excited by the notion of these Hundred Languages. I'm ready to listen.

Better and more inspiring in my eyes is the flexible, inquiry-based approach to curriculum found in Reggio Emilia schools. I find myself drawn back again and again to the amazing projects completed by Reggio students, and I decided to read more on the topic for this week's blog post. Jean Anne Clyde, a professor of education at University of Louisville, partnered with a group of elementary and early childhood educators to write the article, Teachers and Children Inquire into Reggio Emilia (published in Language Arts and accessible here). Clyde et al identify five distinctive characteristics of Reggio Emilia education:

1. Children as Protagonists of Their Own Learning

Howard Gardner describes Reggio's vision of children as "active, engaged, exploring young

spirits capable of remaining with questions and themes for many weeks, able to work

alongside peers and adults, welcoming the opportunity to express themselves in many

languages, to create new ones, and to apprehend and enter into those modes of expression

that are fashioned by their age mates."

2. The Hundred Languages of Children

This phrase, seemingly synonymous with Reggio, comes from a poem written by its

founder, Loris Malaguzzi. Malaguzzi describes children as possessing a hundred different

means to express their ideas and questions. In our literary context, I think we may rephrase

this as children having "a hundred literacies." Reggio students are encouraged to use a

multitude of media to describe their thinking, including (but definitely not limited to)

writing, drawing, photography, sculpting, and acting. Aligning with Gardner's theory of

multiple intelligences, different students will prefer different means of communicating. Part

of the Reggio teacher's duty is ensuring that students have easy access to the materials they

need, and the classroom becomes an atelier (studio).

3. Inquiry-Based, Long-Term Projects as Vehicles for Learning

As briefly explained above, Reggio Emilia does not operate on a curriculum, but allows

students to develop large, long-term projects based on their inquiry. Usually an inquiry topic

is followed by a whole class, and comes from student questions, often after observing a

spontaneous event, like a milkweed pod bursting into seed. The Reggio teacher helps guide

student inquiry through open-ended questions, but students take the reigns for how the

project progresses. Clyde et al write that "investigations result in real-life problem solving

among peers, and numerous opportunities for creative thinking and exploration."

4. Documentation as Communication: "Making Learning Visible"

One of the most time- and work-intensive responsibilities for a Reggio teacher is

documenting the process of student learning. As the students go about investigating and

exploring, the teacher collects physical artifacts of their learning (drawings, writing, etc),

and documents non-physical work through photographs, videos, and audio transcripts. All

of this information is then compiled into documentation panels, poster displays that work as

a timeline of student learning and documentation of the project's evolution. Documentation

panels can be viewed by administration, other teachers and students, parents, and--most

importantly--the students themselves, who often form new questions and ideas when

reviewing their previous work.

5. Teachers as Researchers and Collaborators

Reggio teachers are both guides and co-learners. They keep up with student questions and

ideas, and work to anticipate possible paths that projects could take. They work as

mediators, helping children to ask meaningful questions and develop goals for their

learning. They plan experiences that may trigger student inquiry, and they collaborate with

other teachers to build deeper understanding of students as learners and teachers.

(please note: If I were to make this list, I would also include a sixth characteristic: The Classroom as the Third Teacher. Reggio Emilia places great emphasis on the need for aesthetically pleasing, flexible spaces that allow students to freely explore their inquiry projects and enhance their ability to learn.)

Much like the situated literacy project The Donut House, Reggio Emilia projects treat literacy as a tool for investigation--a means to getting to the end, which is understanding and communication. Clyde et al describe an investigation by a first grade class into the mystery of an empty pond on the school grounds: "[The students] learned to read informational texts, use the index and table of contents, present information using various modes, and assert hypotheses. Their use of diagrams, labels, and drama to support their hypotheses was an efficient and effective way to apply principles of summarizing, analyzing, and accommodating information." For the students in a Reggio Emilia classroom, writing, math, and art are not subjects to be studied, but just a few of the hundred languages that students utilize when exploring their world.

The more I learn about the Reggio Emilia approach to education, the more inspired I become. I still have many questions to answer: What is the place of more traditional literacy instruction in Reggio? What does Reggio look like for older children? Like the students in Reggio schools, I will continue to strive to understand, and I'm sure I'll form many more questions on the way. But I do know that I am very excited by the notion of these Hundred Languages. I'm ready to listen.

Labels:

early childhood

,

inquiry

,

kindergarten

,

literacy

,

preschool

,

project-based learning

,

reggio emilia

,

situated literacy

,

the donut house

,

waldorf

Sunday, February 16, 2014

World of Words

I recently listened to a Voice of Literacy podcast featuring Dr. Susan Neuman of the University of Michigan. In the podcast, Dr. Neuman presents a vocabulary curriculum trial that she has helped develop. Called World of Words (or, WOW), the program is an intervention that aims to extend preschoolers' vocabularies in future content areas such as science and social studies. Dr. Neuman gives an example of the word pear: if preschoolers are taught the contextual relationship between pear, fruit, and healthy, then when they encounter apple or mango, they will be able to draw upon their schema for fruit and better understand the new vocabulary. Dr. Neuman describes this as teaching vocabulary through categories (to me this seems synonymous with themed units), and she emphasizes the importance of this planned vocabulary instruction to achieve better student outcomes. Dr. Neuman also hints at the idea that this will level the playing field between students who are upper- or middle-cass and those who come from lower-class families, where children may not get as much vocabulary enrichment at home.

I did some further research into the World of Words program, which can be found through their website via the University of Michigan. WOW's program description is as follows:

1. Lesson begins with a "Tuning In" clip that demonstrates a phonological awareness skill or

letter sound. Other video clips are played that show the vocabulary content for the lesson. The

teacher and students discuss the video and practice new skills and vocabulary.

2. The teacher engages the students in listening and speaking activities that reinforce content. In

the photo above, the teacher is leading a "call-and-response" exercise.

3. The class transitions to circle time activities that use movement to reinforce content, such as

jumping during a unit on exercise.

4. The children are read a book that has been "specially developed for each curriculum category

to illustrate and review key concepts." They also color take-home books about the concepts.

The WOW website tells us that the children in this photo are looking at picture cards to figure

out how they should color their take-home books.

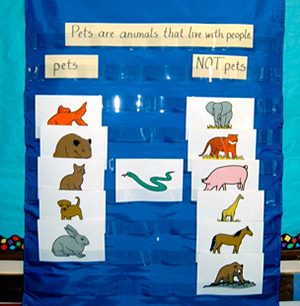

5. The children use picture cards and pocket charts to sort images that represent the vocabulary

content learned in a specific unit, such as "pets."

The second phase of World of Words allows teachers to choose activities and extensions that support the WOW curriculum during centers, free time, or other parts of the day. In a unit about pets...

...or designing a dramatic play center about veterinary medicine.

Others were not so inventive, though this class "pet" was likely very low maintenance.

There you have it: World of Words, developed with the help of Dr. Susan Neuman. Overall, I have nothing against the idea of introducing preschoolers to new vocabulary. Knowing the names for things can only help with communication, which will later aid in reading, writing, and a host of other subject areas. It also gives children more confidence and a feeling of ownership of the world around them. My main issue with WOW, though, can be summed up in one word: authenticity. I believe that the deepest learning comes from student initiative--a desire on the student's part to satiate curiosity. It seems to me that WOW is a prescribed curriculum in which student interest matters little. Better in my eyes would be a vocabulary-rich environment spurred on by student inquiry. If a group of students is asking questions and showing interest in animals and pets, then by all means present content-specific vocabulary about that topic. If a bug in the play yard is piquing interest one day, fill them up with the "grown up" words to describe what they are exploring. You don't need picture cards and videos--find them the real thing. Let them hold, smell, and taste a juicy pear. Let them observe a caterpillar that tickles their fingers as it crawls.

Let them be awed and inspired by the world around them. Let them learn the words that describe it. Let the students lead.

I did some further research into the World of Words program, which can be found through their website via the University of Michigan. WOW's program description is as follows:

" The World of Words (WOW) curriculum integrates multiple sources of information and technology to stimulate children's literacy development in content areas aligned with national pre-kindergarten standards. In collaboration with the creators of Sesame Street®, WOW uses child-friendly media to support children's learning as they encounter new words and concepts in science, mathematics, social studies, and health. Throughout the WOW curriculum, teachers guide children through developmentally appropriate exercises to increase literacy skills while developing their knowledge and vocabulary in academic content areas."I will confess here that until reading this I was unaware that there are national content standards for preschoolers. I think that you readers are already well aware of my thoughts on academic instruction in early childhood, so let's look more at the WOW curriculum:

1. Lesson begins with a "Tuning In" clip that demonstrates a phonological awareness skill or

letter sound. Other video clips are played that show the vocabulary content for the lesson. The

teacher and students discuss the video and practice new skills and vocabulary.

2. The teacher engages the students in listening and speaking activities that reinforce content. In

the photo above, the teacher is leading a "call-and-response" exercise.

3. The class transitions to circle time activities that use movement to reinforce content, such as

jumping during a unit on exercise.

4. The children are read a book that has been "specially developed for each curriculum category

to illustrate and review key concepts." They also color take-home books about the concepts.

The WOW website tells us that the children in this photo are looking at picture cards to figure

out how they should color their take-home books.

5. The children use picture cards and pocket charts to sort images that represent the vocabulary

content learned in a specific unit, such as "pets."

The second phase of World of Words allows teachers to choose activities and extensions that support the WOW curriculum during centers, free time, or other parts of the day. In a unit about pets...

Some teachers got really imaginative and allowed their students authentic experiences, such as taking a field trip to the humane society...

...or designing a dramatic play center about veterinary medicine.

Others were not so inventive, though this class "pet" was likely very low maintenance.

There you have it: World of Words, developed with the help of Dr. Susan Neuman. Overall, I have nothing against the idea of introducing preschoolers to new vocabulary. Knowing the names for things can only help with communication, which will later aid in reading, writing, and a host of other subject areas. It also gives children more confidence and a feeling of ownership of the world around them. My main issue with WOW, though, can be summed up in one word: authenticity. I believe that the deepest learning comes from student initiative--a desire on the student's part to satiate curiosity. It seems to me that WOW is a prescribed curriculum in which student interest matters little. Better in my eyes would be a vocabulary-rich environment spurred on by student inquiry. If a group of students is asking questions and showing interest in animals and pets, then by all means present content-specific vocabulary about that topic. If a bug in the play yard is piquing interest one day, fill them up with the "grown up" words to describe what they are exploring. You don't need picture cards and videos--find them the real thing. Let them hold, smell, and taste a juicy pear. Let them observe a caterpillar that tickles their fingers as it crawls.

Let them be awed and inspired by the world around them. Let them learn the words that describe it. Let the students lead.

Labels:

early childhood

,

intervention

,

literacy

,

preschool

,

vocabulary

Saturday, February 1, 2014

Nurturing Literacy

Ah, phonemic awareness. I came to know this term, before I ever started a teacher education program, as a substitute teacher working in elementary classrooms. To me and my students, phonemic awareness was a time each day, working in yet another leveled group, that I got out a big, spiral-bound book and led the children through boring, scripted exercises. "I am going to say two sounds," I would read. "You say the sounds back to me, then put them together to make a word. Are you ready, Daniel? f - ish. Now you say it back to me." Despite the enthusiasm I attempted to bring to the exercises, the kids would look back at me, nonplussed. "I don't like this game," they would say.

Honestly, at that time, I couldn't blame them. The activities were boring and repetitive. I hated reading the script. The kids hated parroting back to me, and hated even more when they struggled in front of their peers. I felt like phonemic awareness was another drill-and-kill system designed more with bubbles in mind than a child's brain--no imagination, no play, no humor.

Imagine my happy surprise upon reading Chapter Four of Rasinski and Padak's From Phonics to Fluency. In this chapter on phonemic awareness, the authors assert that, "for most students, phonemic awareness is nurtured more than it is taught." Examples of activities to nurture phonemic awareness in students include rhymes, chants, songs, poetry, nursery rhymes, jump rope chants, tongue twisters, popular lyrics, and raps. How refreshing and reassuring to know that, for the general student body, scripted phonemic awareness exercises do not make the list.

There is something this fabulous list reminds me of: Waldorf Education.

Literacy instruction in Waldorf Education tends to get a bad rap from those who don't take the time to understand it, mainly because formalized instruction in reading and writing do not begin until first grade in a Waldorf School. However, this does not mean that kindergarten is an unproductive time for literacy learning! Like Rasinski and Padak say in Chapter Four, "kindergarten is a place for children to become ready for school and ready to learn to read." The Waldorf approach does just that.

Waldorf kindergarteners have circle time each day, in which they learn seasonal songs, rhymes, verses, and chants. The children are playing with sounds and language, taking in rhyme, cadence, and emotion, stretching their understanding of phonemic awareness. Waldorf kindergarteners are also told stories from fairy tales and folk tales, like the Three Billy Goats Gruff. These stories have simple plots and repeated elements that the children can grasp onto. It is common for a Waldorf kindergarten teacher to retell the same story several days in a row. The children become very familiar with the language, characters, and plot, and incorporate them into their own play through drama--living out the story again and again.

The Waldorf kindergarten builds a foundation for the literacy learning that will happen when the children reach first grade, where their familiar characters and stories take on new life in writing. But I think that may be a blog post for another day.

(Want to know more about life in a Waldorf early childhood room? Sneak a peek here.)

Honestly, at that time, I couldn't blame them. The activities were boring and repetitive. I hated reading the script. The kids hated parroting back to me, and hated even more when they struggled in front of their peers. I felt like phonemic awareness was another drill-and-kill system designed more with bubbles in mind than a child's brain--no imagination, no play, no humor.

Imagine my happy surprise upon reading Chapter Four of Rasinski and Padak's From Phonics to Fluency. In this chapter on phonemic awareness, the authors assert that, "for most students, phonemic awareness is nurtured more than it is taught." Examples of activities to nurture phonemic awareness in students include rhymes, chants, songs, poetry, nursery rhymes, jump rope chants, tongue twisters, popular lyrics, and raps. How refreshing and reassuring to know that, for the general student body, scripted phonemic awareness exercises do not make the list.

There is something this fabulous list reminds me of: Waldorf Education.

Literacy instruction in Waldorf Education tends to get a bad rap from those who don't take the time to understand it, mainly because formalized instruction in reading and writing do not begin until first grade in a Waldorf School. However, this does not mean that kindergarten is an unproductive time for literacy learning! Like Rasinski and Padak say in Chapter Four, "kindergarten is a place for children to become ready for school and ready to learn to read." The Waldorf approach does just that.

|

| Circle time in a kindergarten class at the Waldorf School of Louisville |

The Waldorf kindergarten builds a foundation for the literacy learning that will happen when the children reach first grade, where their familiar characters and stories take on new life in writing. But I think that may be a blog post for another day.

(Want to know more about life in a Waldorf early childhood room? Sneak a peek here.)

Labels:

early childhood

,

kindergarten

,

literacy

,

phonemic awareness

,

waldorf

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

.jpg)