In her article, Olshansky explores a modified version of the popular Writers Workshop model of literacy instruction. This modified version is called the Artists/Writers Workshop and includes art and visual literacy as a crucial step in the authoring process. Olshansky writes,

"Artists/Writers Workshop is designed to create a democratic classroom community in which words and pictures are treated as equal and complementary languages for learning."The steps of the workshop (literature share/mini-lesson, work session, group sharing) are not changed to accommodate the Artists Workshop, but the content of the workshop expands to include visual analysis of picture book illustrations and the crafting of images prior to writing. Writer's Workshop places emphasis on the importance of materials for children: students should be offered independent access to a wide variety of writing materials, including papers of different shapes, sizes, colors and textures, as well as choices of writing instruments (pens, pencils, markers, crayons...). This choice is meant both to honor students' decision-making in the authoring process, and also to inspire children in their writing. The Artists Workshop expands this idea to give students independent access to high-quality, "professional" art materials, like paints, pastels, and collage supplies.

I am excited and inspired by the idea of the Artists/Writers Workshop. I feel that this modified model would be effective across the grade levels for a few different reasons. In the younger grades (K-2), children naturally turn to image making as their preferred means of communication. The Artists/Writers Workshop is attuned with this period of child development, offering students the opportunity to craft an image first, and then use that image as an entry point into writing. In the later grades (3-6), I feel that the Artists/Writers Workshop would be beneficial for students who struggle to move words from mind to paper. Creating an image prior to writing allows students to express their ideas visually, and then transmediate those thoughts from pictures into words.

Olshansky includes several quotes from children engaged in the Artists/Writers Workshop in her article, and I think they speak for themselves:

"Writing used to be hard for me, but now it is easy. All I have to do is look at each picture and describe some things I see. I listen to my words to see if they match with my story and they always do. Now writing is my favorite part of school." --David, grade 2

"While I was doing the pictures first, words just started to grow and I got more and more ideas to write and I just writ and writ and writ until it was a finished book." --Kevin, grade 1

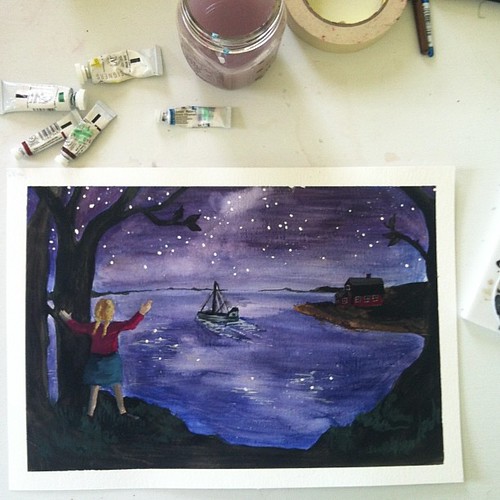

"The pictures paint the words on paper for you so your words are much better. The words are more descriptive. Sometimes you can't describe the pictures because they are so beautiful." --Serena, grade 6(Of course, I think I would be remiss if I didn't share with you a piece of my own art--a recent illustration for Number the Stars by Lois Lowry, painted using watercolor and gouache.)